I’m back with another free read and the second part of my “anatomy of” musings. Last time, I wrote about being a critic in the influencer era. Today, I’d like to grapple with the review itself, or the process of being a critic. While I occasionally veer into broader commentary, this is not a survey of all restaurant reviews, though that would be an interesting assignment. It’s really just a look at how I’ve been approaching Sweet City. It is heavily informed by my experiences at Michelin and writing for the Times but I will say I am not affiliated with either organization and all opinions are my own.

This essay is free, but it is built on years of expertise, which I use every day to put together recommendations and guides for Sweet City’s paid subscribers. If this newsletter has been useful to you in any way, a paid subscription will help keep it going.

Ever since I left Michelin, I’ve been a bit of a lurker. Over the last five years, I’ve attended numerous food conferences and talks around New York City, especially those engaging with the subject of restaurant criticism. I was curious to hear what other people had to say about being a restaurant critic. So, I bought my tickets and listened to them talk about a job that I was intimately familiar with.

I sat in the audience of a food writing conference as Hannah Goldfield talked about picking restaurants for The New Yorker’s Tables for Two column. I sat in a darkened auditorium while Pete Wells’ voice boomed over a speaker, enumerating his dining tactics to a room of curious New York Times readers. As the critic on record, he was still maintaining his anonymity at the time. I listened to a Bon Appétit podcast where Julia Kramer talked about compiling that year’s Best New Restaurants package while pregnant (relatable!). I even dialed into a virtual Eater event about the future of criticism and listened while the host mistakenly noted that New York Times critics were sent to France to train for the job. I believe that was Michelin inspectors.

Anyway, I was drawn to anything that had to do with restaurant criticism, much like everyone else in those audiences. But for most of those people, the job was likely just a curious hypothetical. Maybe even a dream scenario. Well, having been on the other side, I can tell you this: if restaurant criticism sounds like a dream job, that’s because it is.

But, beyond a subsidized meal plan and institutionalized gluttony, being a restaurant critic is still very much a job. And just like any profession, there are things you have to know in order to be good at your job. Only in this case, it’s not a proficiency in InDesign or Outlook. It’s knowing what time your dinner reservation is and under what name.

Like all the critics I have listened to over the years, I want to demystify my process. To pull back the curtain just a little bit to show you the method behind the madness. The engine that powers the dream. Because just as a critic is meant to be a fair and impartial judge, we are also masters of detail.

The Research

Before you can critique anything, you have to have something to critique. Exactly one year ago, before I penned a single word for Sweet City, I created a Google Sheet filled with as many of the city’s bakeries and restaurants with strong pastry programs as possible. I spent the evening hours in front of the TV, after my daughter went to bed, adding rows to the document, looking up menus, and searching for opening dates (great for time pegs!).

This is my directory. It’s currently 200-plus businesses long, filled with notes like “the cake!” and “Fabián von Hauske desserts.” It’s where I go to scroll for ideas, highlight old places I want to check out, and generally take stock of things. For example, I’ve been to all of Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s ABC restaurant derivatives over the years, but I’d like to go back and survey the desserts. I hear they’re quite good.

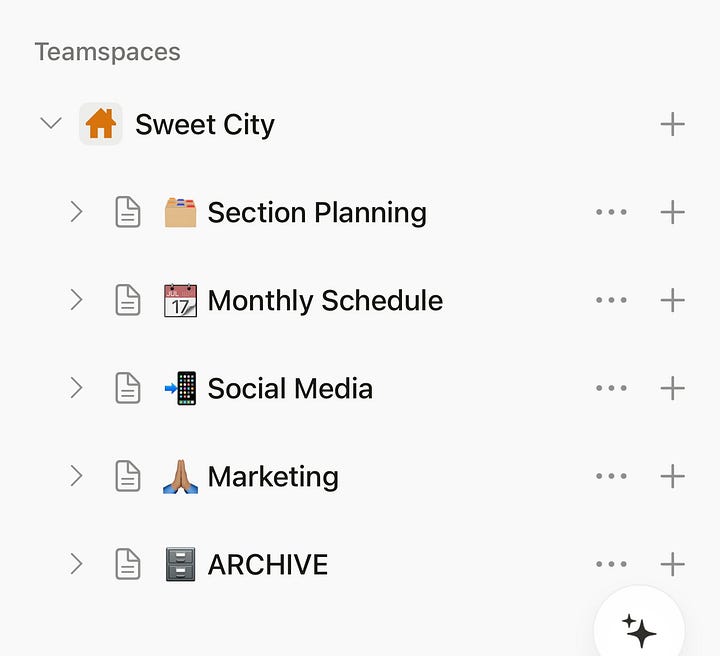

I also have an entirely separate tab for some 150 new places and places I haven’t been to yet. Things like Elbow Bread, a bakery from Zoë Kanan opening downtown any day now. And The Lobster Club in Midtown, which I’ve never been to, mostly because it costs $16 for a mushroom spring roll. But I know Major Food Group invests heavily in pastry, so it’s probably worth a visit. This sheet, along with my editorial calendar, which I maintain in Notion, and my essay ideas tab are my most active pages. I’m adding, planning, scheming in here all the time.

And then, there’s the trash tab. The document filled with places I’ve been to, but didn’t feel like writing up, for one reason or another. Places like a popular Italian café in Williamsburg, not to name names. I was underwhelmed!

My attempt to make a comprehensive directory of New York bakeries might say more about my own neurosis than it does about being a critic. The more significant point here is, even before eating anything, it takes real work to pick and choose what to review from the vast number of eating establishments in New York. At least a quarter of my job is just making lists.

To that end, understanding a critic’s rubric is a bit like asking a journalist where they get their stories. Which is to say, it’s that unspeakable “je ne sais quoi.” It’s a cultivated and proprietary knack for what will be interesting to an audience and what won’t. Built on years of reading, observing, trying, and failing. Sometimes, it depends on the intent of the review — is it a scoop of a new and unheard-of place? Or is the critic weighing-in on a big-name opening? Other times, it’s just the whims of the critic.

I know I haven’t mentioned the actual food yet, which should really determine whether or not a place is reviewed. But this initial research and sorting process is critical, too. You can’t see, eat, and write about it all. And when the food is worth some commentary, making the choice to write about a restaurant inevitably means you are not writing about something else. Who or what gets the attention, good or bad, is a real consideration.

Personally, I try to keep an open mind. This used to be more controversial than it is today, but I’ll take a lead anywhere I can get it. And I’ll follow a lead wherever it takes me. Creative filters on Yelp sending me to Elmhurst, Queens for ube pandesal? Cool. Deep cut comments of a Reddit thread saying the city’s best butter cake is in Midtown? It’s on the list. My Google Maps search skills are impeccable. My iPhone has over 150 saved screenshots from Instagram and elsewhere. I’ll walk through neighborhoods, ask for intel at the bar, I read PR emails, and yes, I’ll even do some research on TikTok.

Because, ultimately, I make up my own mind about the food.

The Visit

Visiting a bakery is far more informal than inspecting restaurants for Michelin ever was. I can just show up on a Wednesday afternoon, buy a box of croissants, and leave. There are virtually no concerns about anonymity or flying under the radar to get the real experience.1 Chances are, those pastries would taste the same whether I was a critic or not. And while I still make it a point not to tell anyone what I do, or why I ordered two desserts for one person, even if I did, I’m not sure they’d really understand (or, in many cases, care).

While I don’t have to bother with aliases or disguises, I do maintain some standard practices. I will visit a place at least two times, if not more. I will try to eat through as much of the dessert menu or pastry case as possible. And I still wait a few weeks after a bakery opens before my first visit. I’d rather experience a bakery that is comfortably in its groove versus struggling to keep up. I try to plan ahead so that I can show up with friends, like a normal person, but most of the time, I’m just dragging my family along with me.

There is an art to ordering off a menu, even at a bakery. (At a restaurant, there are usually only four desserts on the menu so I make an effort to order them all.) In an ideal world, I’d try a variety of things at various points of time because bakeries are so good at highlighting seasonal produce. But usually, I just start with what the bakery is known for. At Mah-ze-Dahr, for example, I would be sure to get the brioche donut. After that, I’d go for what I know and like because I can be a better judge of something I eat often. Then, finally, I’d choose something unusual. Maybe an ingredient like pickled strawberry jam. Or maybe something that would make good copy, like the Salty Lunch Lady’s f*cked up cookies.

I rarely ask for recommendations, but I will ask what is selling well. Most of the time it’s pretty obvious, but sometimes, it’s a pleasant surprise — like the time I saw a woman buy five chocolate chip cookies at Pâtisserie Vanessa, the Frenchiest French bakery on the Upper East Side. I grabbed the last one with a canelé and wow, I’m so glad I did that.

During the visit, which sometimes only lasts as long as it takes to pack up a slice of cake, I try to observe as much as I can. Are the pastries coming out fresh? What looks like it’s about to sell out? Is the staff overwhelmed, informed, kind? Who is in the line with me? What music am I listening to? Like a fly on the wall, or better yet, like the John J. Audubon of New York City bakeries, I sit, and watch, and draw my conclusions.

I also pay for all food myself. As in, it’s coming out of my bank account, not a corporate account. If I’m comped anything — and I can count the number of times this has happened on one hand — I generally don’t write about it. This is a key and fundamental difference between being a truly impartial critic who is free to form any opinion about an experience versus being indebted to a PR team or chef and beholden to a favorable review.2

Finally, my last and least favorite part of a visit is taking pictures. In the past I only did this for reference, but now I have to take pictures of everything before I take a bite of anything. It’s a huge pain and I really miss the days of carefree eating with zero regard for poor lighting.

Thankfully, though, the camera on my iPhone is pretty good. Come to think of it, I really should deduct my cell phone bills because I use my iPhone for everything. All the sorting, planning, and photography I do on my phone frees up my mind for the real work — the critique. AI could never.

The Critique

Here is where I could write an entire book. I began to unpack the critic’s approach to criticism in my last essay. So, without going too far backwards, this part of the process revolves around one question — is it good?

Of course, the answer always begins with the actual taste of the food, which really begins during the visit. I can pretty quickly determine if I see enough promise in a restaurant or bakery’s food. Is there a level of basic technical skill on display? Is there a reasonable understanding of how flavors and textures should work? Is this better than other versions? Is it delicious in a conventional way or in more of an interesting, cerebral way?

At Michelin, this analysis was further refined to a five-point criterion, which is famously only concerned with the food. As much as people think the white tablecloths and an abundance of forks can make or break a star rating, based on my experience, it really doesn’t. I often find myself explaining this with a concept I learned in marketing — correlation is not causation. It’s very probable that a restaurant investing in its ingredients and an experienced staff is also investing in the trimmings we associate with fine dining like German stemware or Japanese ceramics.

There are some gaping holes in that argument, I know. But still, it’s not like we were all going around saying, not enough space between tables! No star!

But anyway, I was trained to evaluate food based on criteria like technique, quality, personality, and consistency. What I felt was missing in those assessments, explicitly at least, was an evaluation of whether or not the food was Good, with a capital G. With some sort of moral underpinning, whether that was social or environmental.

One example I think about often is chef Chintan Pandya of the Unapologetic Foods restaurant group. Pandya is not only a good chef, but a chef who is Good for the South Asian diaspora. His group has been pushing the limits of Desi food in New York in terms of both its perceived value (aka ability to charge higher prices) and popularity amongst a broader audience.

There is a heavy debate to be had around this dual notion of goodness. Primarily, what is the weight of context over the actual food? Cultural caveats, or caveats of any kind, can be a disservice to a chef’s absolute talent. Like, when media qualifies a great chef as a “great female chef.” We don’t need the sympathy vote, but we do need an acknowledgement of the world we exist in and its many obstacles and barriers.

I still haven’t quite sorted it out myself, but I do think criticism and general taste-making by way of awards, lists, and guides does its audience a disservice if these contextual matters aren’t at least considered. Without it, platforms risk becoming irrelevant.3

“We're talking less about whether a work is good art but simply whether it's good — good for us, good for the culture, good for the world.”

Wesley Morris, NYT

Here is where I should get into the merits of using stars or some other rating scale versus words to convey a critique. But this essay is getting LONG so let’s just say there’s a time a place for both. Stars make things relative, which is useful, but lacks nuance. Reviews indulge a good critic’s affinity for discourse and encourages readers to engage more deeply with a restaurant. Clearly, I prefer the latter. In my experience, the verdict is rarely ever as simple as a number.

An important inverse worth noting is what happens when something is not good. A critic needs to be able to articulate why a dish or menu failed. The job may fall short of a consultant’s remit to fix or strengthen a weakness, but it requires a consultant’s mindset — identify the fault lines in the food, the concept, or whatever else is making that particular experience inadequate.

So, how does this all relate to Sweet City? Well, now you know all that’s going through my mind when I’m staring at a brownie or a coconut custard or a black sesame mille-feuille. But also, through desserts, I naturally get to cover a diverse array of people and topics that are perfect deep thinking subjects. I get to write about things like consumption versus pleasure, taste hierarchies, and self-expression through the art of pastry.

When I worked at Michelin, once the critique was written and filed, the work was mostly done. We could move on to the next meal. But now, I have to carry the torch to the very end, when the last sentence is laid, fact-checked, and delivered to the inboxes of family, friends, and strangers on the Internet. And as I learned while writing reviews for the Times, putting an experience into words in a smart, engaging, and compelling way might just be the hardest part of being a critic.

Here is where I’ve learned the most.

The Review

When Pete Wells announced that he was leaving his position as New York Times critic, former critic Ruth Reichl made a comment in her Substack newsletter that reviewing restaurants was more about the writing than the eating and I’ve never co-signed anything faster. I started in this industry as a critic, not a writer. It has been so humbling to be confronted with the blank, white wall of expectation that is an empty Word doc.

I’ve learned that the best way to become a better writer is, yes, to write, but also to read. When I started contributing to Hungry City, I made it a point to read one restaurant review a day. I had a running list of lines that I loved in Evernote. Stuff like, “He wants each sensation to have its say without overstating its case — to frame, tame and joust with the other players,” by Frank Bruni. Or, “It is either on point or your grandmother goes home,” by the late Jonathan Gold. I dream of the day when I can wield a great metaphor in service of a particularly good cookie.

But the hardest thing about writing a restaurant review is not necessarily conveying the food in an elegant way. It’s using the form to say something of significance. As I’ve said in the past, anyone can have an opinion about the taste and texture of a dish. The harder, more complex question to answer is — so what?

“What is needed, first and foremost, is a shift in mindset, an existential about-face from recommending places for dinner to investigating how society finds meaning through food.”

Theodore Gioia, Los Angeles Review of Books

It has taken some practice, but I think I’ve gotten better at big picture, zoomed out takes that aren’t just roadmaps to a menu. Even if it is something as simple as reminding readers that life was pretty different 20 years ago. As I wrote in my review of ChikaLicious, which is sadly no longer a dessert tasting bar, “One consequence of longevity and consistency in a city that refuses to sit still is that as the world changes around you, it also reveals your age. What was groundbreaking back then is now just old fashioned or, if time has been kind, classic.”

I’ve also made it a point to incorporate first hand research into as many of my reviews and articles as possible. I learned this by following Ligaya Mishan’s lead at Hungry City, where she merged reporting with lyrical descriptions and critical takes on the food. Today, even if it’s just a quick email exchange, I try to add a chef or baker’s voice into my newsletters. First and foremost, it’s an opportunity to fact check my notes on the food, but it’s also a chance to probe for fun little details that aren’t always visible on a menu. Things like pastry chef Sam Short’s fondness for citric acid at the Brooklyn bakery Pan Pan Vino Vino.

In my experience writing about people who make food, I know there’s a better, richer story if I take the time to get a quote.

And last of all lasts, I fact check everything that goes into Sweet City. I do miss having an editor who will catch things like when I write “geography” when I meant to say “topography,” or when I reach a bit too far with a description. But we do what we can! So, every Tuesday, I print out the week’s newsletter and I run through it with three different colored pens. Like the photography, it’s painstaking work. But every time I find a misspelled name or forget the accent on a French word, I am reminded of the value of being careful.

In the Los Angeles Review of Books article quoted above, which is worth a read in full, the author writes at length about how the restaurant review is an imperfect vehicle for the kind of critical food reporting this industry desperately needs. And I agree. I don’t know if the grind of producing a weekly review or an annual Best Of list is equipped to deal with the inequities that spring from capitalism and transactional labor in this country.

But as a vehicle of discovery at least, I think the critic can use a review to guide readers towards restaurants, chefs, and cuisines that fall beyond one’s natural lines of exposure. We can challenge readers to think differently about the food they eat, to encourage them to ask the right questions of a restaurant meal. Not just, is this dish tasty, but can this dish teach me something new about myself? About other people?

At the end of the day — which is actually the start of each Wednesday, when Sweet City hits your inbox — what I want to offer you is perspective. And it all begins with a spreadsheet.

Restaurant criticism is about much more than how food tastes these days and a newspaper or magazine critic doesn’t necessarily need to be anonymous to impart those observations. Historically, this was all a bit of a farce anyway. A company like Michelin, however, doesn’t give critiques per se, they assign distinctions like stars and Bib Gourmands. The value is inherent in the award. Personally, I still stand by the importance of experiencing a restaurant like a regular person in order to accurately assess the food. You can usually get far enough with a good pseudonym. But also, this.

Beyond paying one’s bills, restaurant critics should also maintain some distance from the industry. At Michelin, we would announce any conflicts of interest, say, an ex-boss chef. Before I wrote anything for the Times, I was asked if I had any ties to chefs in the industry, like co-authoring a cookbook. Even for the most ethically obliging journalist, when these lines are blurred, it becomes tricky terrain to navigate that can, at times, amount to something like biting the hand that feeds you.

Which is why in 2021 the James Beard Foundation added new criteria to its awards that looks for winners who are contributing something of value to their community. And at Michelin, I believe the move to cover more regionally representative foods, like street stalls and hawker centers in Asia, was a step in this direction.

This was so great. I'm going to use it as a test in my cultural criticism class.

Wow, this is a MUST READ for any food writer worth their salt...